Table of Contents

Overview – Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamics refers to what the drug does to the body—specifically, how it interacts with cellular targets such as receptors, enzymes, and ion channels to produce physiological effects. A deep understanding of pharmacodynamics is essential for interpreting drug mechanisms, anticipating side effects, and making rational therapeutic choices. This article covers key concepts including receptor binding, agonism vs antagonism, efficacy, potency, drug targets, and desensitization.

Definition

Pharmacodynamics is the study of the interactions between drugs and their targets in the body, including how drugs bind to receptors and the biological responses they elicit.

Principles Behind Drug Action

- Chemical-receptor signalling controls body functions → No signal = no effect.

- Disease alters signalling → Pharmacological compensation can restore function.

Drug–Target Interaction

Affinity

- The strength of binding between a drug and its receptor.

- High-affinity drugs bind even at low concentrations.

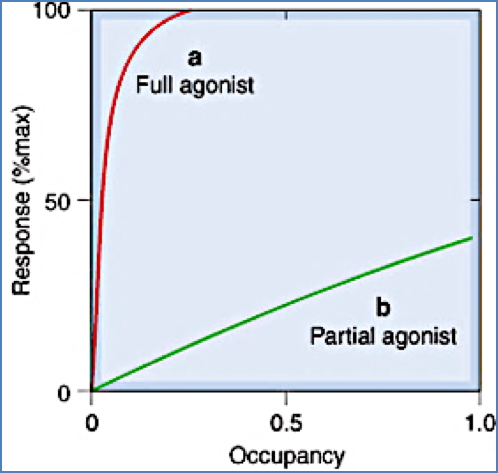

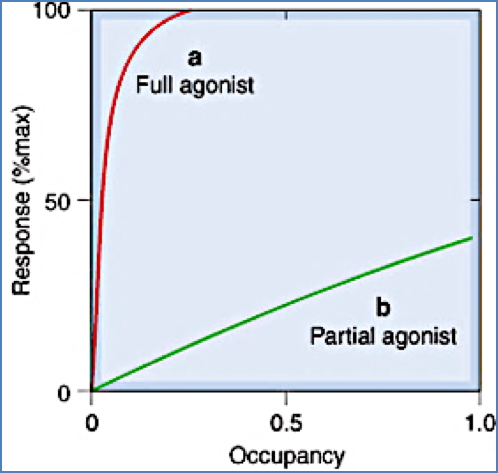

Efficacy

- The ability of a bound drug to activate the receptor and elicit a response.

- Full agonists: Maximal response at <100% receptor occupancy.

- Partial agonists: Submaximal response even at 100% occupancy.

- Antagonists: Bind without activating the receptor → zero efficacy.

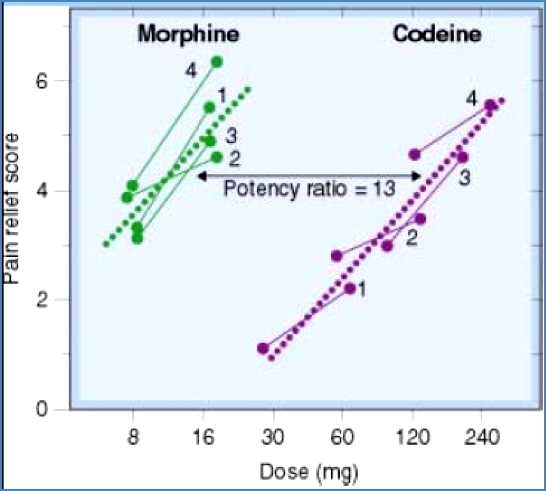

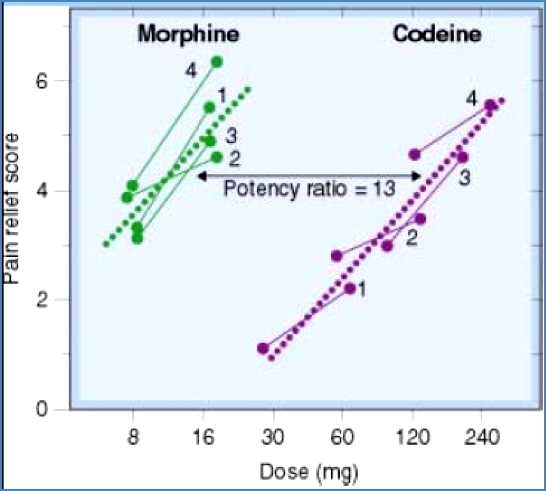

Potency

- The amount of drug required to produce a given effect.

- Depends on both affinity and efficacy. Example: Morphine is more potent than codeine because it achieves the same effect at a lower dose.

Common Drug Targets

1. Receptors

- Protein molecules that detect and respond to endogenous mediators.

- Drugs act as:

- Agonists → Trigger receptor response

- Antagonists → Block receptor response

2. Ligand-Gated Ion Channels

- Ion channels opened by ligand binding.

- Drug types:

- Antagonists → Keep channels closed

- Modulators → Alter opening probability

- Indirect agonists → Affect channel-linked pathways

3. Enzymes

- Drug types:

- Inhibitors (e.g. captopril, AChE inhibitors)

- False substrates → Occupy the enzyme without useful output

- Prodrugs → Activated by enzymes

4. Transport/Carrier Proteins

- Membrane-bound proteins that move substances across the cell membrane.

- Drugs act as:

- Inhibitors → Block transport

- False substrates → Cause accumulation

Note: Some drugs (e.g. chemotherapy, antimicrobials) act directly on DNA, bypassing proteins.

Agonists vs Antagonists

Agonists

- Bind and activate the receptor.

- Vary in:

- Affinity

- Efficacy

- Potency

- Partial Agonists

- Submaximal effect, even at full occupancy

- Can antagonise full agonists

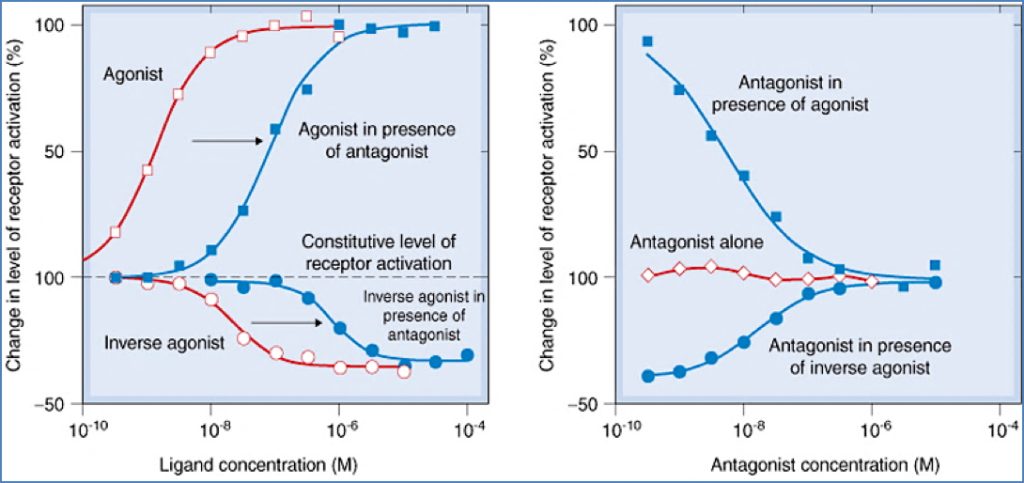

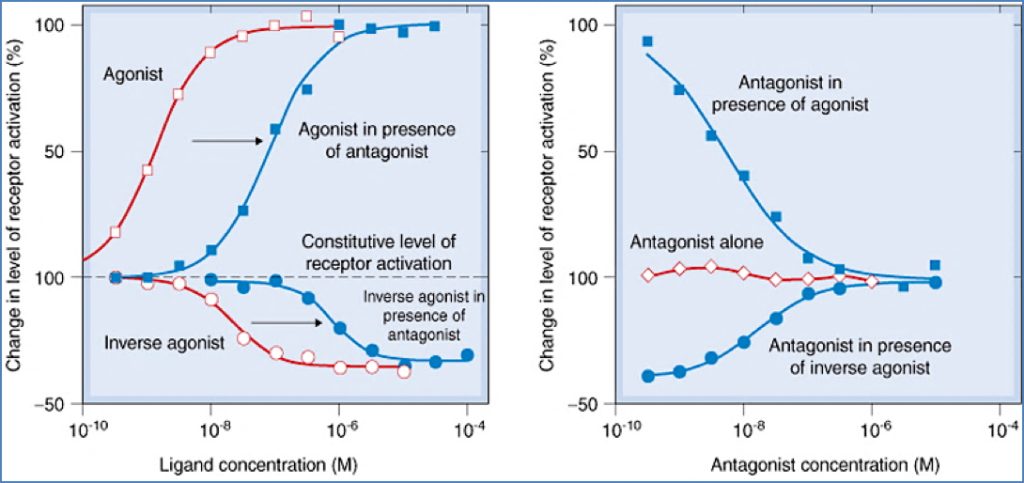

- Inverse Agonists

- Suppress constitutive receptor activity

- Have negative efficacy

- Distinct from antagonists (which have zero efficacy)

Antagonists

- Bind but do not activate receptors.

- Prevent endogenous or exogenous agonist binding.

- Types:

Receptor-Mediated Antagonists

- Competitive: Reversible; overcome with high agonist doses

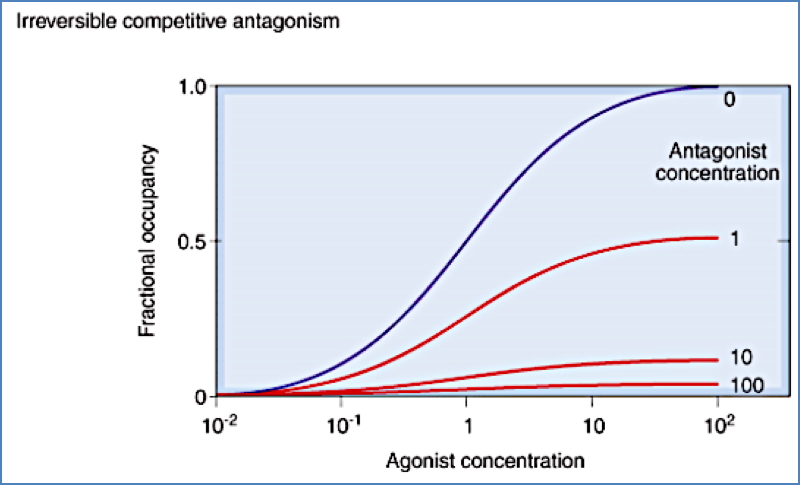

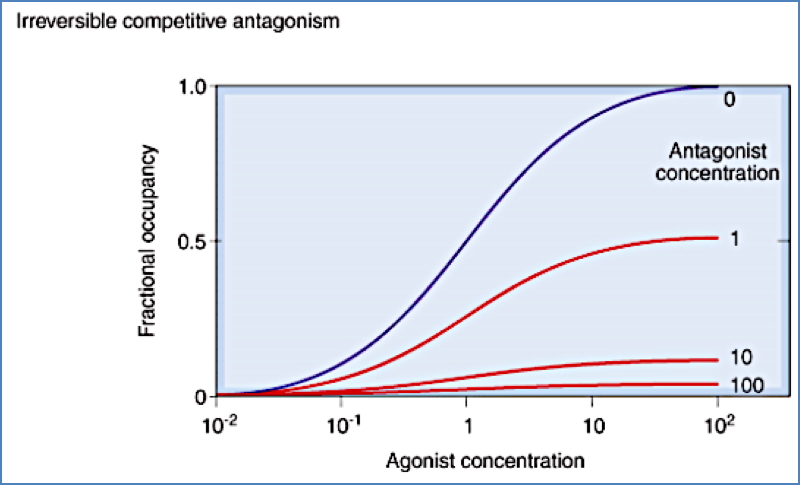

- Irreversible: Bind tightly; agonists can’t outcompete

- Non-competitive: Bind elsewhere or interfere downstream; not overcome by agonist

Non-Receptor-Mediated Antagonists

- Chemical antagonism: Binds agonist directly (e.g. chelation)

- Pharmacokinetic antagonism: Alters drug absorption, metabolism, distribution

- E.g. Alcohol ↑ warfarin clearance via liver enzymes

- Physiological antagonism: Opposing effects (e.g. histamine vs PPIs on gastric acid)

Drug Specificity

- Biological specificity: Does the drug act selectively on one tissue or receptor subtype?

- Target specificity: Most target proteins are highly selective for their natural ligands.

- Clinical benefit: Targeting receptor subtypes can maximise effect and minimise side effects.

Receptor Families

| Family | Endogenous Ligand | Drug Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Adrenergic | Noradrenaline | Beta-blockers, alpha-agonists |

| Cholinergic | Acetylcholine | Nicotine |

| Dopaminergic | Dopamine | Levodopa, pramipexole |

| Serotonergic | Serotonin | Metoclopramide, sumatriptan, LSD |

| GABA-ergic | GABA | Gabapentin, zolpidem, topiramate |

| Glutamatergic | Glutamate | Ketamine, memantine |

| Opoidergic | Opioids | Morphine, codeine, fentanyl |

Receptor Subtypes

- Receptors from the same family but expressed in different tissues.

- Allow for organ-specific targeting and side-effect reduction.

Example – Adrenergic Receptors:

- α1 → Vasoconstriction (e.g. decongestants)

- β2 → Bronchodilation (e.g. asthma medications)

Desensitization and Tolerance

Types

- Tachyphylaxis: Rapid loss of effect with repeated doses

- Tolerance: Gradual reduction over time

- Refractoriness: Temporary loss of responsiveness

- Drug resistance: Loss of antimicrobial/anticancer effect

Mechanisms

- Receptor changes:

- Conformational → Receptor no longer activates

- Phosphorylation → Disrupts downstream signalling

- Downregulation: Receptors internalised/degraded

- Mediator exhaustion: e.g. Depletion of neurotransmitter stores

- Increased metabolism: Drug is broken down more quickly

- Physiological adaptation: Homeostatic compensation

- Active extrusion: Drug pumped out (common in chemo resistance)

Summary – Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamics describes the interaction between drugs and their biological targets, including how they bind receptors, produce responses, and trigger tolerance. Understanding affinity, efficacy, potency, and mechanisms of desensitization allows clinicians to use drugs more precisely and predictably. For a broader context, see our Pharmacology & Toxicology Overview page.