Table of Contents

Overview – Microbiology of Parasites

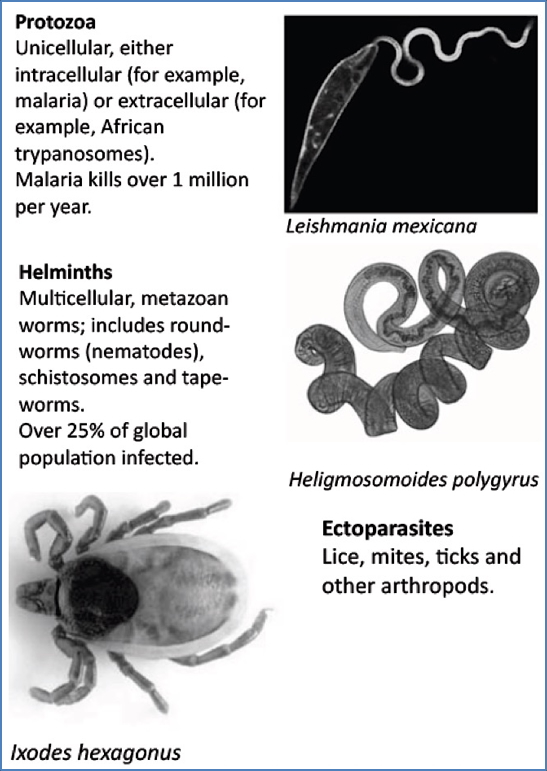

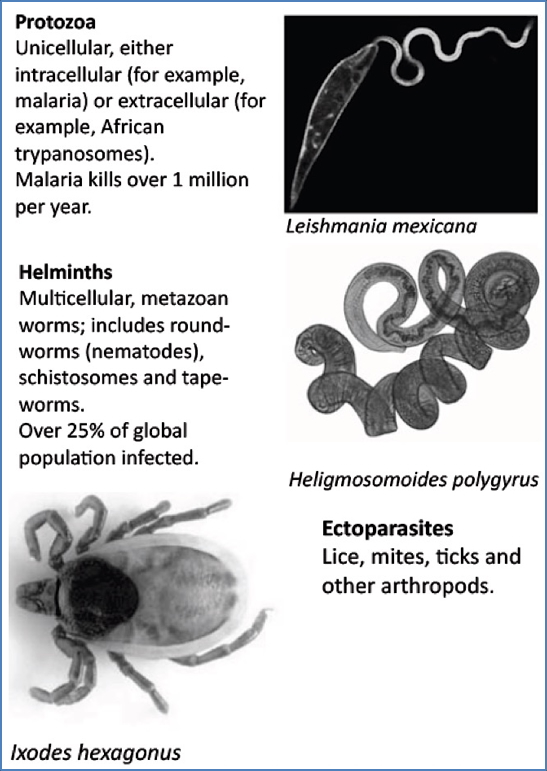

Microbiology of parasites covers a diverse group of organisms—including protozoa, helminths, and arthropods—that live at the expense of their host. Parasitic infections often involve complex life cycles with multiple hosts, chronic disease courses, and sophisticated immune evasion strategies. Understanding their biology is key for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of parasitic diseases worldwide.

Definition and General Features

- Parasites derive nutrients and shelter from their host without offering benefit in return

- Typically cause long-term, chronic infections (unlike most bacteria and viruses)

- Often utilise host-derived growth factors to promote their own replication

- Success depends on:

- Minimal disturbance to host

- Avoidance of immune detection

- Life cycles often involve two or more hosts:

- Definitive host – harbours the adult/mature form

- Intermediate host – harbours larval/immature stages

Classification of Parasites

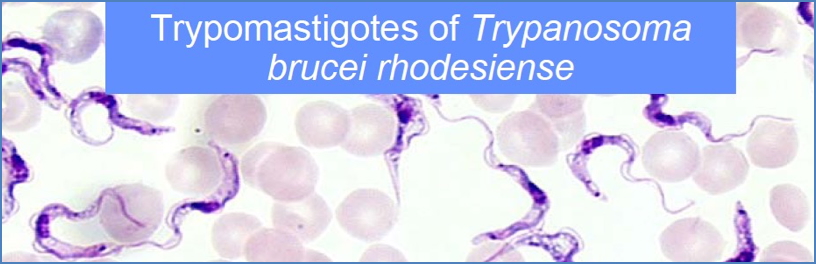

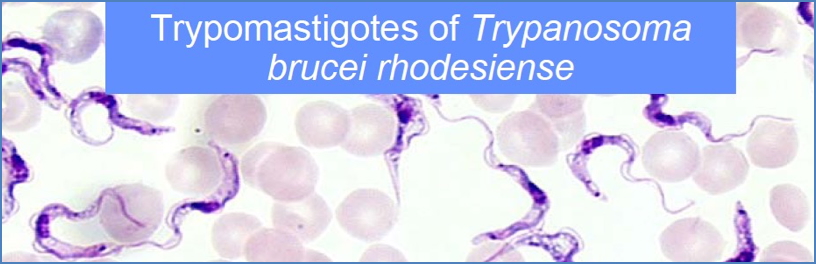

Protozoan Parasites (Unicellular)

Grouped by locomotion method:

- Amoebae – move via pseudopodia (e.g. Entamoeba histolytica)

- Ciliates – move via cilia (e.g. Balantidium coli)

- Flagellates – move via flagella (e.g. Giardia lamblia)

- Sporozoa – no motile structures (e.g. Plasmodium malariae, Toxoplasma gondii)

Metazoan Parasites (Multicellular)

Includes helminths and arthropods.

Helminths (Worms)

Divided into three phyla:

- Platyhelminthes (Flatworms)

- Trematodes (flukes)

- Cestodes (tapeworms)

- Nematodes (Roundworms)

- Acanthocephala (Spiny-headed worms)

Arthropods

Segmented invertebrates with exoskeletons (e.g. ticks, lice, mites)

Parasite Replication Cycles

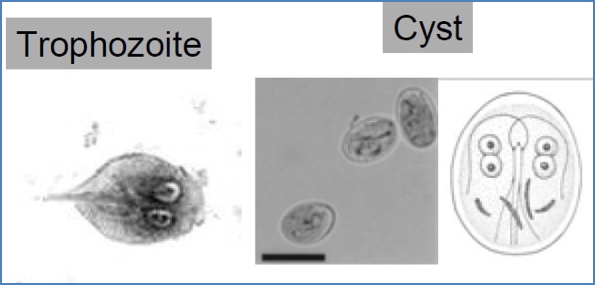

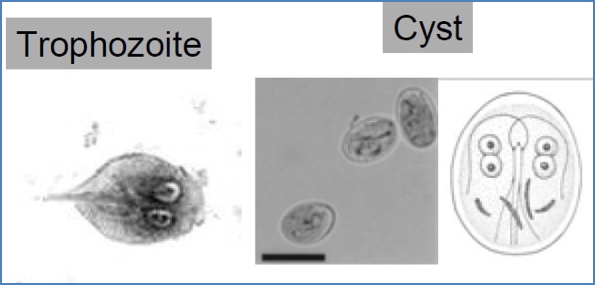

Protozoan Life Cycle

- Trophozoite Stage:

- Active, feeding, and replicating form

- Lives in the definitive host

- Cyst Stage:

- Dormant, hardy form for transmission

- Survives harsh conditions

- Shed in faeces; excystation reactivates infection

Metazoan Life Cycle

Trematodes (Flukes)

- Eggs → faeces → snail host → cercaria → human infection

Cestodes (Tapeworms)

- Eggs in faeces → ingested by cow/pig → human infected by undercooked meat → adult attaches to small intestine

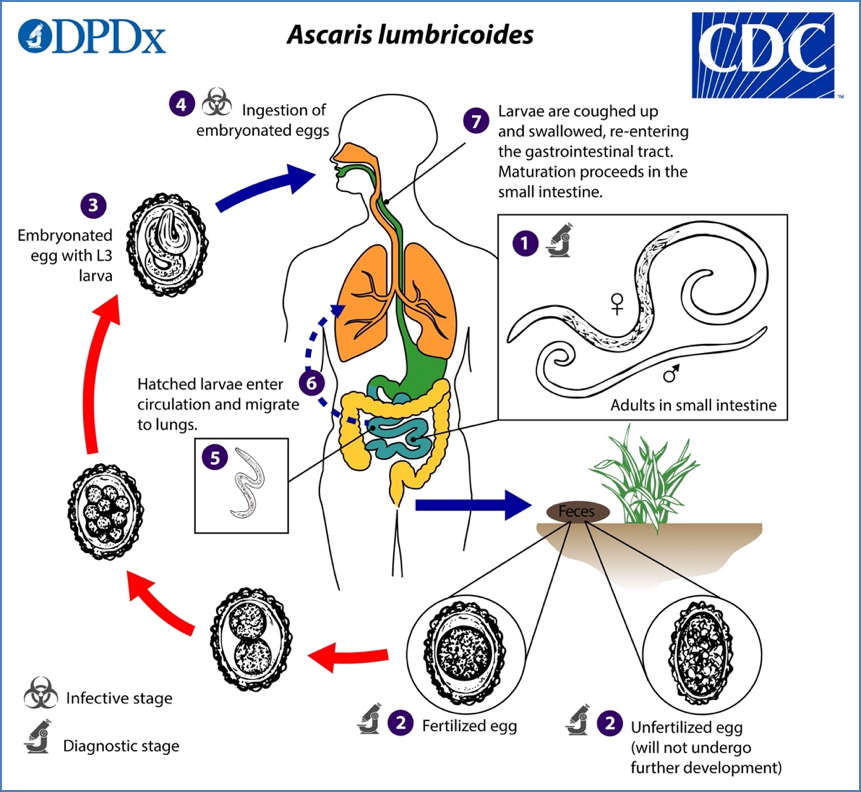

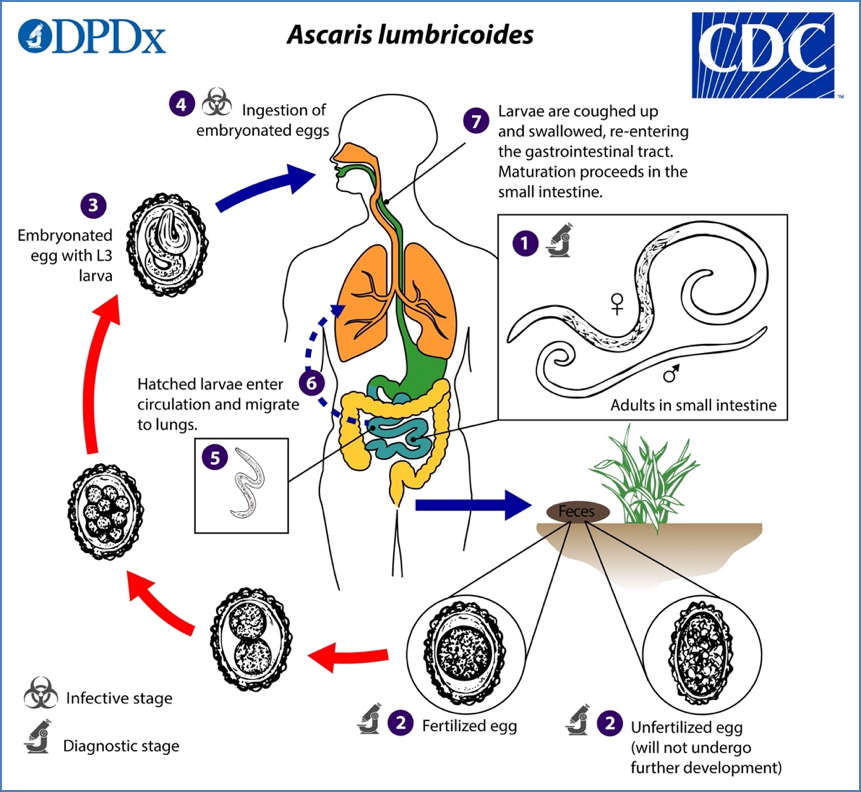

Intestinal Nematodes

- Direct life cycle (no intermediate host)

- Faeco-oral transmission with larval migration through lungs and back to GI tract

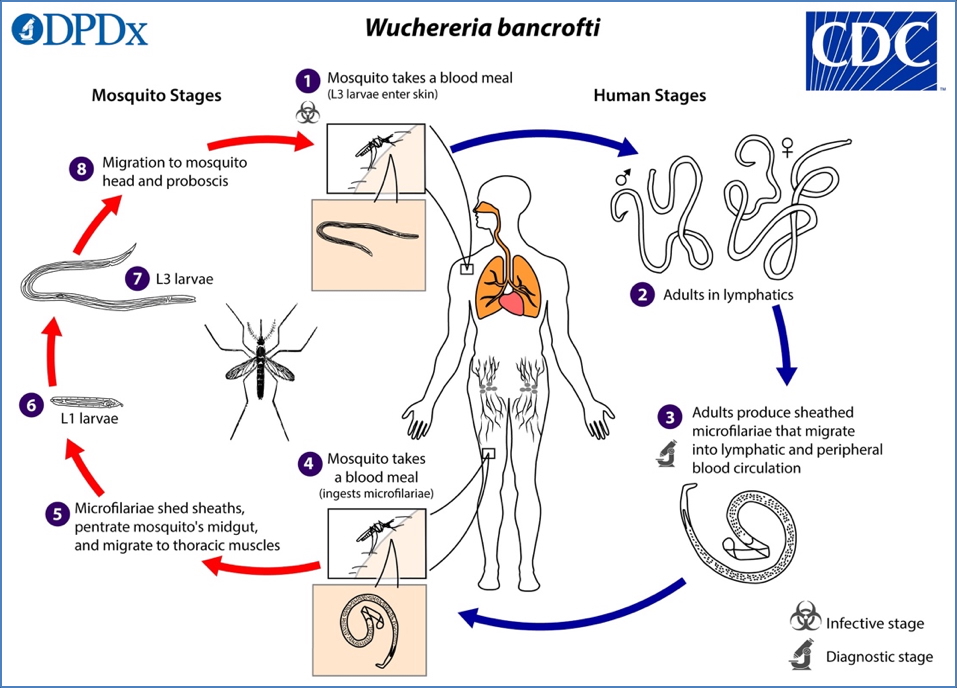

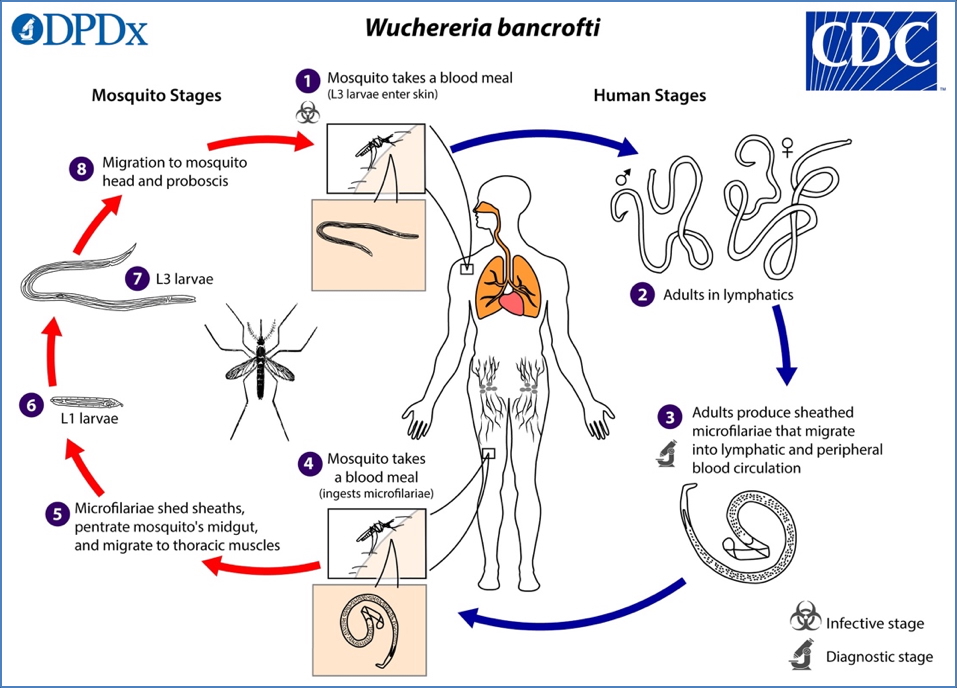

Filarial Nematodes

- Bloodborne microfilariae → ingested by mosquitoes → transmitted to another human (e.g. Wuchereria bancrofti)

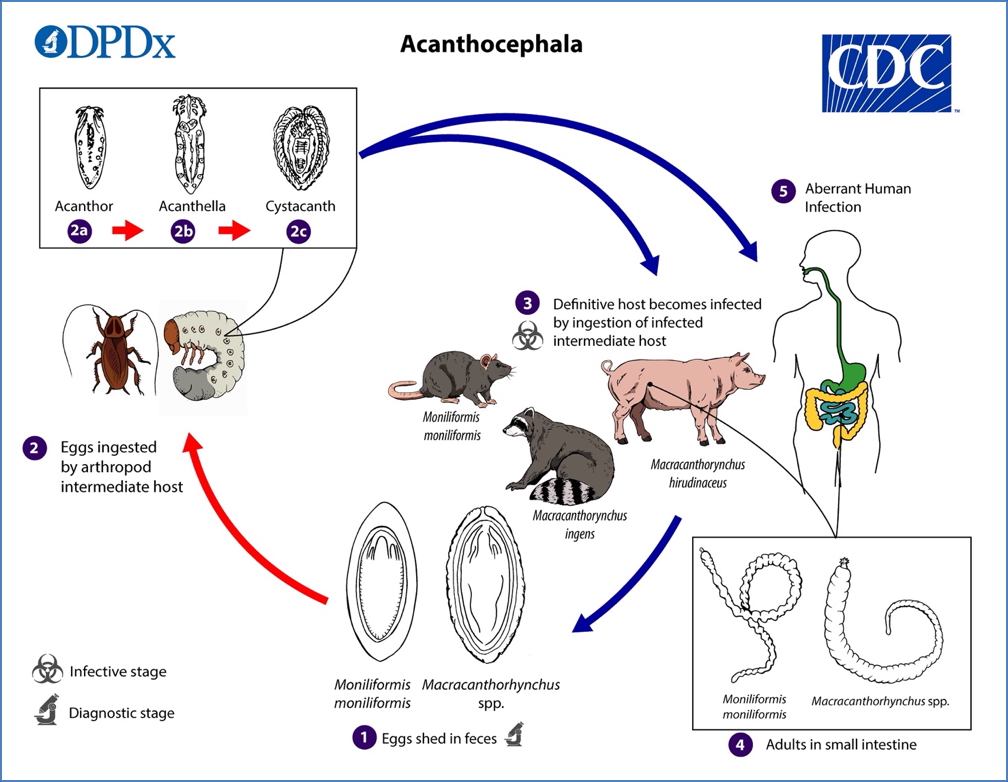

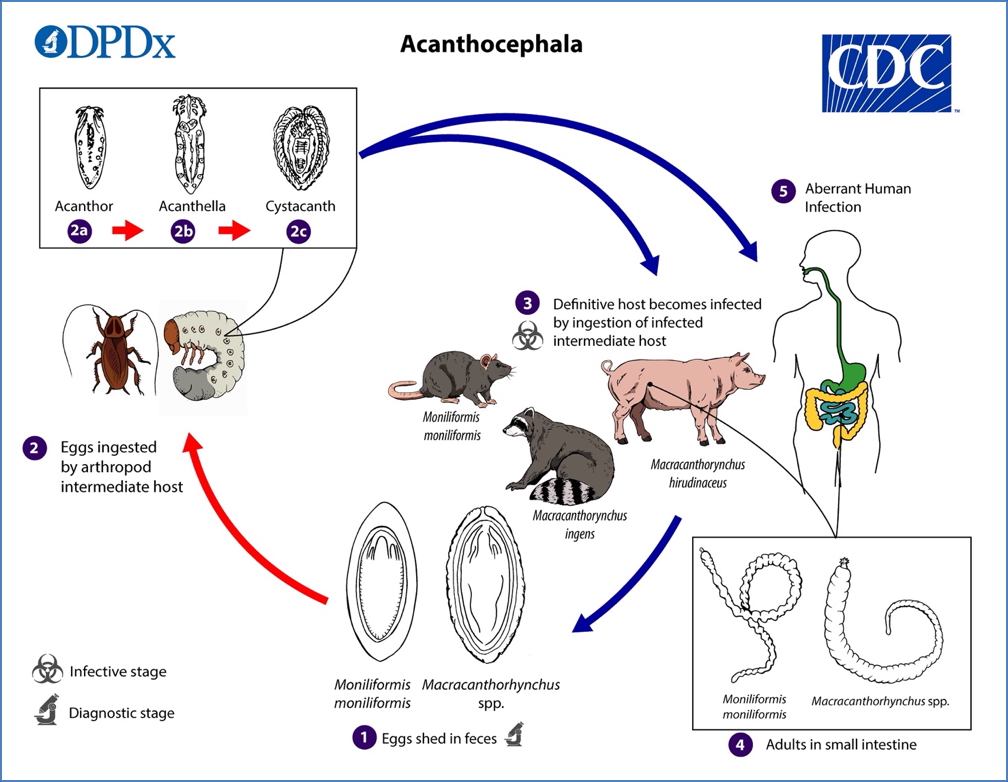

Acanthocephalans

- Embryo → crustacean intermediate host → definitive host eats crustacean → adult develops in gut

Routes of Entry (Helminths)

- Oral ingestion (contaminated food/water)

- Skin penetration (e.g. schistosome cercariae)

- Vector transmission (e.g. mosquitoes for filaria)

Immune Evasion Strategies

Protozoa

- Antigenic variation and drift

- Molecular mimicry – expressing host proteins

- Intracellular localisation in immune-privileged sites

- Vesicle shielding and lysosomal fusion avoidance

- Manipulation of host immune responses

Helminths

- Antigen shedding to confuse immune targeting

- Secretion of proteases to degrade antibodies

- Superoxide dismutase neutralises neutrophil attack

- Skew immune response to Th1 dominance, reducing IgE production

- Use of host cytokines as growth factors

- Induce immunosuppressive cytokines

Specific Immune Evasion Mechanisms

- Molecular mimicry: e.g. schistosomes coat themselves with host proteins

- Protease production: e.g. Schistosomula cleave antibodies, inhibit macrophages

- Sheltering in immune-privileged sites:

- Plasmodium falciparum lives in red blood cells (RBCs) — hidden from CD8+ T cells and antibodies

- Infected RBCs sequester in peripheral vessels to avoid splenic clearance, potentially leading to ischaemia

- Immune exploitation: Some helminths stimulate inflammation to increase adhesion molecule expression, aiding egg release into tissues and eventual excretion

Summary – Microbiology of Parasites

Microbiology of parasites encompasses protozoan and metazoan organisms that exploit human hosts for survival and reproduction. Through sophisticated immune evasion mechanisms and complex life cycles, these parasites can persist long-term and cause significant disease. For a broader context, see our Microbiology & Public Health Overview page.